By now, everyone has become aware of the Korean Wave: 한류 Hallyu. The popularity of K-Pop and K-Dramas has taken the world by storm. I was personally interested in their popular music scene as far back as 2013, but it was not easy to get friends to listen as they were unfamiliar with the language. It seems the world has now decided to embrace them. Although, I do note that it has required Korean artists to sing in English and Spanish in order to gain a larger audience. To me, this is a testament to their determination to do what it takes to survive and succeed.

Today’s article will focus on the music that came before the K-Pop phenomenon we know right now. This was the music that eventually gave ground for the popular music of Korea today, but it has very complex roots in Japnese occupation, Korean popular and traditional songs, and foreign influence. Today’s focus is on Korean Trot music.

Foreign or Native?

It may be difficult to understand the timeline without a little backstory. The Joseon Empire (Korea) lasted until 1897, however the people still utilized the title despite the Russian and Japanese aggression that was taking place at the time. The Russo-Japanese war lasted from 1904-1905. Korea became a protectorate state of Japan in 1905. By 1907, the emperor of Korea was forced to abdicate his throne and Korea was colonized formally by Japan in 1910. The Japanese colonization would last from 1910-1945. This was followed by the Korean War in 1950-1953. During both periods, the Trot remained very popular among the Korean people.

Korean Trot made its debut through foreign music introduction. Its roots were partially found in American Foxtrot and Japanese colonization of Korea. It was considered traditional music of Korea after 1950. However, it has always received mixed acceptance due to the origins of the music. Despite this, it has maintained a steady foothold in the nation for generations.

An interesting phenomenon has taken place with this music. There have been research studies done to more deeply analyze the way in which the Korean people have embraced or decried the Trot as their own. One unique argument proposed that “Arirang” became nationalized as belonging to Korea although its roots were found in the “Song of Empire” rooted in Japanese colonization. The songs that qualified under the “Song of Empire”category were exclusive to songs created under colonization (Atkins, 2010).

A similar phenomenon occurred with “Tears of Mokp’o”, which was also considered a “Song of Empire” that gained popularity in Japan. The interesting part of this is that these songs were not associated with any particular country, but more with all “imperial subjects” (Sorensen, 2012). As a result, it is impossible to define these songs as being Korean or Japanese in origin. “Imperial subjects” were those who were defined by ethnicity, which did not include the Japanese as they were considered “people of the interior”, which means they were not deemed separate from the “Imperial subjects” and did not need to be defined by ethnicity (Sorensen, 2012). However, Koreans have often associated these songs with nationalism and have held them in high regard as Korean songs.

Not all Trot music met the same appreciation as “Tears of Mokp’o” (1935) by Lee Nan-young (1916-1965). Although more music evolved from this era, by 1964 it was no longer seen as acceptable to Koreans if it suggested Japanese influence. This was seen in the eventual banning of “Camellia Lady” [Tongbaegagassi] by Lee Mija despite its popularity among the people. The military government at the time did not allow anything that reflected assocation with Japanese influence. The ban would eventually be lifted in 1987.

Roots and Structure

The Trot’s popularity was very strong during the periods of colonization and war as it provided the people an outlet for their negative feelings during such difficult times. It first appeared in the 1920’s as T‘ŭrot’ŭ (Trot). However, it also went by the names yuhaengga or taejung gayo in the period between 1920’s - 1970’s. The name Trot is said to have derived from the English dance called the “Foxtrot,” however there is no direct relationship. The Foxtrot rhythm in Korea has been referred to as Ppongtchak, which is actually an onomatopeia representing the “oom-pah, oom-pah” beat of the song’s rhythm. However, the complexity of the division goes far beyond the rhythm.

The argument derives from the mode (scale), duple meter, and 7-5 syllablic stanza lyrics that are identifiable within Japanese Enka music. The music that was produced under the Trot genre prior to 1945 utlized the pentatonic scale paired with trichord motifs in a descending pattern. This was similar to Japanese Enka music. However, there are others who proclaim that duple meter and 7-5 syllabic stanza lyrics are not exclusive to Enka’s music. They state that these factors also existed in the nongak (farmers’ music) and koryŏ gayo (Goryeo Dynasty folk music).

Japanese music’s influence wasn’t exclusive to Japan. In fact, Japanese Enka, originally known as Ryukoka, found its inspiration from Western music. Japan had already begun to proactively adopt Western culture and music during this time. The version of this that had been initiated in Korea was known as yuhaengga. It later changed its name to Trot.

It has also been found that the father of Enka, Koga Masao, had derived his compositional style from Korean musical influence. The term Enka was not coined until 1973 when Japan tried to redefine its national identity, so there really is no definitive conslusion on the origin of Trot. However, Trot and Enka are clearly related regardless of where the influence began. More importantly, they record the histories and emotions of the people at that point in history. For this, they are very important to cultural identity.

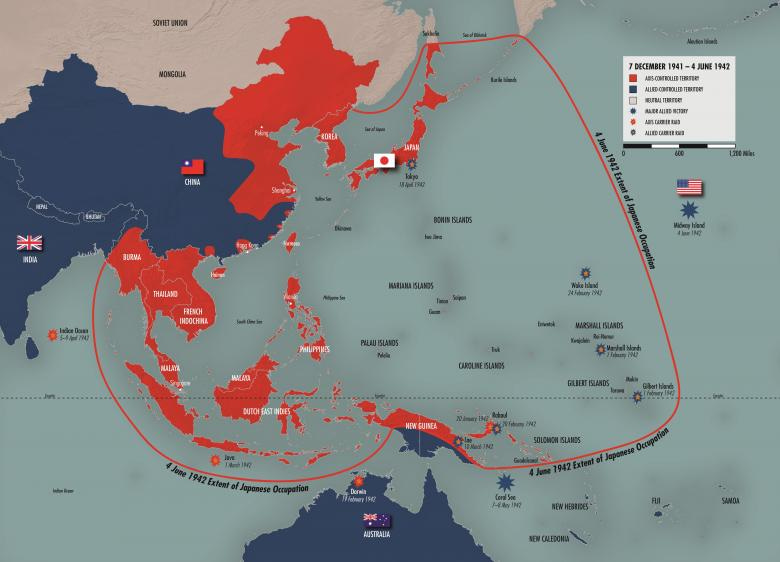

The Imperial region also included many other countries, as seen in the map above. As such, the influence of Japanese Enka, Kayōkyoku, and Hokkien-kwa (or Taiyu-ge) were found in the music of other colonized regions.

Popular Music

After the 1930’s, Trot was firmly rooted in Korean culture. Much of the music dealt with love and loss, which ultimately fed the development of K-Pop’s ascent when Trot was merged with popular dance music.

“Song of Mokp’o” was composed by Son Mok-in. The lyrics were written by Moon Il-seok, who had won Okeh Records song contest that year (1935). The two-beat rhythm that carries the song across minor and pentatonic scales was accepted overwhelmingly by the population with its theme of lovelorn longing and stood as a metaphor for their colonized homeland. Many referred to it as the “song of the nation.” It was this song that really launched Trot into the magnificent status that it celebrated for decades to come.

Liberation of Korea in 1945 launched the metamorphasis of Trot’s characteristics. The pentatonic scale was used less and less and other tempos and rhythms began to emerge. The original lyrics of Trot were traditionally expressing love, homesickness and the sorrows of a colonized people. However, they evolved into what we find in today’s K-Pop music, simple daily expressions of candid emotion.

Although Trot has remained strong in its determination to evolve with the times, it has faced challenges throughout the various tumultuous periods of Korean history. The military government did ban some music for having too much Japanese influence. Others had tried to incorporate other music genres such as rock and folk music. However, when a few of the famous singers found themselves entangled in a scandal, the authoritarian government created a “popular music purification movement.” This of course impacted the musicians who were producing music that was not fitting the limits of the restrictions imposed. It also influenced the music that was allowed to no longer decry sorrow, but to project more positivity.

The sixth republic of South Korea (1987 - today) was the beginning of liberation from military authoritarianism and liberation for musicians. Korea had just hosted the 1986 Asian Games and the 1988 Seoul Olympics. This launched a period of Korean society’s pursuit of fun and enjoyment. As a result, Trot saw an incredible resurgence. “Eomeona” by Jang Yoon-Jeon is a perfect example of Trot launched in 2004. As seen below, the music had shaped-shifted from maudlin music to cheerful and entertaining.

Modern Trot

Despite its age, Trot seems to be here to stay. In modern Korean media, you will find Trot in many telvision shows, competitions, and variety shows. In fact, it is difficult to find any modern Korean television show without a Trot singer in it.

Trot music has been associated with two identities: han and heung.

Han is sorrow.

Heung is of joy, merriment, and good cheer.

Han and Heung are also at the heart of modern K-Pop

The emperor of Trot, Na Hoon-a, made a special televised appearance during the holidays in 2020. His resurgence is a testament to the longevity of the genre. In fact, you can see how Na Hoon-a is staying relevant today. Take a moment to listen to a song he performed in 2022. It is also a perfect title for the reality that Trot has encompassed for over 100 years.

However, it’s not just for the older generations. The younger generations are also embracing Trot in its new Golden Era. This is especially true in their competition shows as we see below.

It truly is amazing how a genre of music can sustain itself over so many extreme political changes and over 100 years. The longevity and adaptability of Korean Trot is definitely something to marvel at.

REFERENCES

Atkins, E. T. (2010). Primitive Selves: Koreana in the Japanese Colonial Gaze, 1910–1945 (Colonialism). University of California Press (2010).

Chang, Yujeong (2016) A study on the traditionalism of “trot” – Focused on Yi Nanyǒng’s “Tears of Mokp’o”, Journal of Marine and Island Cultures, 5:1, pp. 60-67, ISSN 2212-6821, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.imic.2016.04.002.

Hŏ, Ǔnsim. “‘Pusanyŏk’hamyŏn ttŏollinŭn norae, 『ibyŏrŭi pusanjŏnggŏjang』 (The Song that Comes to Mind When You Think of ‘Busan Station’, 『Parting at Busan Station』).” Foundation of Korean Cultural Center, 31 Mar. 2018, ncms.nculture.org/korean-war/story/4204.

Hyun, In. “Kusseŏra kŭmsuna (Be strong, Geum Soon!).” Orient Record, 1953.

Kim, Michael. “Re-Conceptualizing the Boundaries of Empire: The Imperial Politics of Chinese Labor Migration to Manchuria and Colonial Korea.” Sungkyun Journal of East Asian Studies, vol. 16, no. 1, 2016, pp. 1-24.

Ko, Boksoo. “T’ahyangsari (Living Away from Home).” Midopa Record, 1934.

Lee, Aerisu. “Hwangsŏngyett’ŏ (The Ancient Site of Ruined Castle).” Victor Record, 1932.

Lee, Haeyeon. “Tanjangŭi miari kogae (Heartbreaking Miari Hill).” Oasis Record, 1956.

Lee, Ju-wŏn. “Han·il yanggugŭi taejunggayo pigyogoch'al-1945~1950nyŏnŭl chungsimŭro-(A Comparative Study of Korean and Japanese Popular Music -With a Focus on 1945~1950-).” Journal of Japanese Studies (JAST), 64.0 (2015): 75-98.

Lee, Jun-hee. “Tanjangŭimiarigogae (Heartbreaking Miari Hill).” Encyclopedia of Korean Culture, The Academy of Korean Studies, 21 Feb. 2018. http://encykorea.aks.ac.kr/Contents/Item/E0072232.

Lee, Nanyoung. “Mokp’oŭi nunmul (Tears of Mokp’o)” Okeh Record, 1935.

Lee, Seung-Ah. (2016). Decolonizing Korean Popular Music: The Japanese Color Dispute over Trot. Popular Music and Society. 40. 1-9. 10.1080/03007766.2016.1230694. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/308709304_Decolonizing_Korean_Popular_Music_The_Japanese_Color_Dispute_over_Trot

Nam, Insu. “Ibyŏrŭi pusanjŏnggŏjang (Parting at Busan).” Universal Record, 1954.

Son, Min-Jung. “Regulating and Negotiating in T’ûrot’û, a Korean Popular Song Style.” Asian Music, 37.1 (2006): 51-74. Ye, Jinsu. “‘Hwangsŏngyett’ŏ’ Purŭn Kasu Iaerisu Saengjon Hwagin (Singer of Hwangsŏngyett’ŏ, Lee Aeri

Soo, Confirmed to Be Alive).” Munhwailbo, 28 Oct. 2008, www.munhwa.com/news/view.html?no=2008102801072730025002.

Sorensen, Clark W. (September 2012). “Mokp’o’s Tears.” Paper Prepared for the Spaces of Possibility Conference, Simpson Center for the Humanities, University of Washington.

Verma, Snigdha. (April 2024). All you need to know about Trot. https://halsugprod.com/blog/all-you-need-to-know-about-trot

Yong. (2021). Trot Is Hot Again: How The Music Genre Made A Comeback In Korea. https://creatrip.com/en/blog/8731